Flexible Frugal Flourishing Irrigation in a Pressure-Pot Warming World

This blog proposes a charter of 15 principles for flexible frugal flourishing irrigation in a pressure-pot warming world. Flexible means irrigated systems and irrigators adapted to dramatic fluxes in water availability in a warming world – from drought to wet cycles. Frugal means consuming less water per hectare, per system and per catchment during drought, abundant and normal cycles. Flourishing means protecting / boosting crop production and other water uses and benefits throughout those cycles. Pressure-pot means irrigation will have to deliver more food from less water as it faces more accountability and fresh scrutiny in a world facing stiffer water competition.

Inspiration. The idea for this blog came from my drive through N-E Spain in July 2025 when I passed hectares and hectares of sprinkler-irrigated wheat. See photo above. The irrigated wheat sat alongside fields of rainfed wheat as a patchwork of irrigated and non-irrigated fields. The rainfed wheat was doing okay but you could see the extra yield achieved with irrigation. I’ve never seen so many sprinkler-risers – thousands of them. There are lots of factors at play such as antecedent winter rainfall refilling stocks of water in Spain’s dams but it never occurred to me that one would irrigate wheat if the crop can do reasonably well with rainfall. This because in a semi-arid country like Spain, prone to periodic drought, the opportunity cost of that water used by, or stored for, Spain’s towns, industries, higher value crops, or ecological flows, must be higher – certainly given the likelihood of periodic drought.

Irrigation as climate adaptation. Thinking about the photo above, there are four ways of looking at irrigation as an adaptation response to climate change and drought. One is that adding irrigation to rainfed agriculture is a wholly appropriate adaptation in the face of periodic drought. The second that irrigation exacerbates water consumption and inequities, and is inappropriate especially when consumption is already large and continues to grow without regulatory oversight. The third is that, based on simple narratives, certain types of irrigation are ‘adaptively OK/not OK’. So leaky smallholder irrigation is apparently resilient and OK, but modern irrigation is efficient and not OK – or, equally bizarrely, it is the other way around. Fourth, irrigated systems need to fit climate change in more coherent ways. This blog is about this fourth way.

Other work. I know there are many ongoing discussions about agriculture, food and water in a warming world. Others, e.g. IWMI and World Bank, are working on similar ideas. For example, the World Bank is working on their Nourish and Flourish framework, and IWMI is working on a Commission to address water for food. These are welcome in order that irrigation, by far the largest global consumer of freshwater, does not escape attention. However, note the draft 2025 World Water Congress Marrakech declaration on “Water in a Changing World: Adaptation and Innovation” does not mention irrigation. Other high-level reports on food also miss water and irrigation.

Water control is key. I believe flexible frugal flourishing irrigation in a warming world can only be delivered via improved water control. Without water control, irrigation won’t be flexible enough, frugal enough and flourishing enough. Without an honest discussion around water control, we will allow irrigation off the hook. However a wider definition of water control is needed, not one allied to irrigation engineering or other disciplinary conceptions of irrigation hydrology.

Therefore I propose ‘integrated irrigation water control’ (IIWC) is: the regularly assessed careful management and control of irrigation water during drought, abundant and normal periods to meet specified crop and other water demands occurring throughout the areas, scales, time periods and geographies of irrigated systems facilitated by the design, operation, maintenance and institutions of irrigated and green infrastructure, in order to capture, regulate, share, apportion, schedule, match and benefit from multiple water supplies, accommodating hydrological, environmental, social, political and engineering factors. This definition is an invitation to think about the idea of irrigation and the future of irrigation. Although its emphasis is on a technical understanding of water control, it means governing irrigation from various perspectives captured by the 15 principles. It is (hopefully) non-prescriptive, and does not make calls such as ‘we need efficient irrigation’.

The 15 principles

The 15 interlinked principles reflect on how irrigated systems might deliver, and benefit from, integrated irrigation water control, and therefore prepare for a more unpredictable, dynamic and hotter world.

- Water apportionment and scheduling in a warming world; will it be supply- or demand-led? This first principle is the only one phrased as a rhetorical question. It is an urgent question that asks whether, in a water scarce world, should we be allocating and scheduling irrigation to eke out a variable and limited supply (supply-led) – or apportion water to meet what crops ideally need (demand-led). Although there will be a mix depending on geography, hydrology, history and trajectory, this first principle asks us not to accept at face value the objective of meeting precisely what the crop needs – there may not be enough water to do this both seasonally and more suddenly when drought kicks in. (This question is why I am sceptical of soil water sensors to real-time schedule irrigation). This question also appears to ask whether farmers are seen ‘bottom-up’, having agency to ask for what water, regulations and technologies they want – or whether farmers are seen ‘top-down’ needing to adapt to new scarcities, solutions and rules. There are two answers to this question: 1) It is scarce, variable and less-predictable water that will exogenously constrain and shape farmer choices and practices. 2) The approach taken needs to be balanced and co-created between farmers and others.

- Sustainable within a dynamic range within a context. Integrated irrigation water control ensures that on average, over the long run, or during stable periods, irrigation fits its own particular catchment and aquifer context – hydrologically, legally and institutionally. This sustainability principle (Rosa, 2022) brings to the fore the need for water control to bear down on aggregate water depletion to deliver real water savings whilst sustaining crop growth (Lankford and McCartney, 2024). There is considerable misunderstanding about the hydrology of real water savings (Lankford, 2023) which needs addressing (see point #4 below). Even after flexible, frugal and flourishing water management has progressed, to fit within a hydrological envelop may require difficult decisions to retire irrigated infrastructure and areas. I also explain sustainable irrigation here.

- A non-equilibrium resilience approach for cycles of abundance and scarcity. Water control is needed to accommodate dynamic non-equilibrium climate and weather (Lankford and Beale, 2007). 1) This will allow irrigation (e.g. land, withdrawals, duration) to purposively contract and expand to match forecasted periods of aridity or wetness. 2) This will benefit from better prediction of climate (see #9 below). 3) It expects irrigation demand to match a changing 2-3 month supply window, most likely through a zoned risk approach (e.g. 45% land gets mild deficit irrigation (DI), 35% gets strict DI, 20% gets zero irrigation). 4) This treats drought as ‘shock-learning’ for the long run so that operations, technologies and institutions can be reformed. 5) Drought-acquired frugality extends into normal and abundant periods; meaning non-equilibrium resilience is not the same as sustainability but both are connected in the long run. For example, either irrigated systems use drought to ratchet up aggregate water consumption over time becoming unsustainable in non-drought periods and less resilient to future drought (Lankford et al., 2023). Or we encourage systems to find a sustainable ceiling of aggregate water consumption (in other words frugality) in non-drought periods to provide water for other sectors and store excess water ready for the next drought, thereby enhancing drought resilience.

- Multi-factor irrigation efficiency, productivity, allocation and banking. It is too easy to promote irrigation efficiency (IE) as climate-smart (or climate-dim) without it being well understood (Lankford et al., 2020). Thus, a more multi-factor understanding of irrigation efficiency and water control is required. 1) Many factors reduce aggregate water consumption; irrigation efficiency, practices, area, withdrawals, timing and duration (Lankford, 2023). 2) Water control, for irrigation scheduling for crops and often for other uses such as domestic supply across space and time, will have to become more accurate. Furthermore, water control across the scales and periods of an irrigated system should involve minimal or effective monitoring – see next principle. 3) Water control will enable more widespread deployment of deficit, protective or alternate wet-and-dry (AWD) irrigation which both needs and encourages good water control. 4) Water control manages the paracommons which asks; who gets the gain of reduced consumption (or who loses from efficiency gains?) (Lankford and Scott, 2023). The paracommons envisage four parties compete over these savings; the proprietor making the savings, an immediate neighbour, society, or nature. Another option banks the gains in storage for later use by one or all of the four parties. 5) Water control and efficiency are mediated by four types of irrigation systems discussed in the four pathways below. 6) Water control will need robust but easy-to-understand indicators such as ‘hectares irrigated per day’. One option at the catchment scale is via the indicator Days to Day Zero.

- Multi-scale designed-in architecture and tools. Delivering integrated irrigation water control should not be onerous. We need to consider how to make irrigation systems easier to run at higher levels of performance. A common response is automation, sensors and the Internet of Things, but there are risks here. Simply adding more sensors and actuators may not give us the comprehensive easy-to-manage water control we seek, and these may undermine irrigators’ efforts to fine-tune their systems. Rather we need an architecture of water control from macro-scale satellite tools, micro-scale sensors and meso-scale of system infrastructure. (I believe this architecture and its dashboard could be contained within a farmer-oriented irrigation app).

- Modular architecture for bite-sized problem identification and management. Within this architecture, we need to consider risk-based ‘holon modularity’ whereby large systems are divided into smaller modules physically and institutionally (Lankford, 2008). (A holon is both a whole and part of a whole). Water users within each module/holon co-manage their own allocation of water ‘intra-module’. This subsidiarity allows land and water problems to be better identified and resolved using local ideas in a non-prescriptive way – including market/regulatory solutions which are often problematic when applied globally and nationally. Identifying modules/holons could use a risk-based approach to the density of water complexity within the catchment or aquifer. For example, a 5000 ha commercial fruit farm may only need a revised water licence, letting its managers respond to that. But a 500 ha smallholder system may need many more services in order to adapt.

- Share management alongside supply and demand management. Responses to water sustainability problems are usually seen through supply and demand management. However a more dynamic world needs share management to ensure transparency, equity and justice as water systems quickly adjust to and flex with water abundance and scarcity (Lankford, 2013). Reflecting on the previous principle, share management is needed if larger systems are divided into modules because inter-module sharing of water and other resources may be necessary when water scarcity is unevenly divided. Share management takes place throughout nested scales – irrigators sharing a tertiary unit, multiple tertiary units within a secondary unit, secondary units within an irrigation system, between irrigation systems, between sectors, and between catchments and aquifers.

- Management of water supply and storage; types, access, volumes and refilling. Water control also extends to water supplies and supply management. Four points apply. First, the volume, location and timing of irrigation withdrawals and depletion will have to match current and future water supplies, both as flows and stocks. This principle emphasises supply management alongside demand and share management. If supplies and sources are not managed well, then refilling of stocks and flows in wetter periods will not be sufficient causing greater water shortages during drought periods. Second, irrigators are accessing more types of water (e.g. springs, rain, soil, deep and shallow groundwater, recycled wastewater, on-farm storage). Alongside more efficient irrigation, this greater use of water explains increases in irrigated areas. Some see ‘many waters’ as resilience, but if unregulated and unmonitored, then in a connected hydrological cycle, greater consumption of these waters diminishes water availability for others. The third point is that more capture and storage of water is needed everywhere and of every type, e.g. dips and hollows, ghost ponds, soil storage, streams, on-farm and operational tanks and inter-annual storage (Lankford et al., Forthcoming). Fourth, in a more dynamic climate, we need healthy soils and landscapes (green infrastructure) to attenuate, slow down and hold water when it arrives in abundance (Sikka et al., 2018).

- Managing uncertainty; forecasting and advance water/information communication. The benefits of enhanced water control should draw from and feed through to improved forward notices and planning. Not only will climate forecasting be central to the future of setting irrigation withdrawals and consumption at different risk levels, regularly updated communications regarding water availability and scheduling will also help farmers plan their farms, cropping patterns and irrigation scheduling. In the long run, at-risk legacy irrigation infrastructure not able to secure high assurance water allocations may have to be retired. [I have not worked in or travelled to the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB), and I appreciate there are differing views as to whether their approach to water allocation during drought is successful, but it seems the MDB has much experience on uncertainty and drought-facing irrigation management. (Mallawaarachchi et al., 2020)]

- Multi-factor, multi-scale water, land, crop performance monitoring / dashboards / apps. To manage irrigation control and performance upwards, we need information-rich sufficiently accurate models which present easy-to-digest monitoring and management dashboards, and that are attractive to farmers so they are adopted (Lankford et al., 2025). On the other hand, over-simplified models will permit irrigation its ongoing inertia – and to carry on colonising freshwater resources. New dashboards and apps can face different irrigation users and purposes. As said above, I believe a single manager- and farmer-oriented phone app can collate, analyse and present simple and relevant performance information. Also regional dashboards might present comparisons of different irrigation systems to aid peer-to-peer learning. It is from this kind of app that irrigation data can be generated and analysed for strategic planning purposes.

- Technical support and clarity over the change process and outcomes. IIWC targets need to be discussed/expressed so that systems, either incrementally or rapidly, move towards specific performance objectives. For example; “within 5 years this system in normal periods will run at a peak supply hydromodule of 0.760 l/sec/ha over 2500 hectares, and during a drought at 0.550 l/sec/ha over 1600 hectares.” These objectives can then provide farmers with clarity over their planning. Water proxies such as kilowatt-hours energy usage also fall under this principle. This change towards set objectives requires a tailored participatory service approach to irrigated systems. Every irrigated system, including individual schemes and catchments, is unique. Furthermore, we need to work with groups of farmers and linked irrigated systems within a catchment landscape. If we work only with individual farmers or systems, there could be a) less trust, b) inequitable outcomes, and c) loss of peer-to-peer learning. (See principle #14 below on business support alongside technical support).

- Supported by farming, marketing, technology, trade, water regulation and political systems. Improving water control cannot happen in isolation – it is tied to wider political, agricultural, trade, socio-economic and knowledge systems. Some of these systems are changing fast, so information and choice are key here. For example, in parts of Uzbekistan I was impressed with new cost-effective types of drip tape allowing drip irrigation to mesh with canal deliveries improving in-field irrigation efficiency. Other system drivers (e.g. energy prices, land tenure) need to be addressed so that catchment water regulation and allocations support irrigators aiming to perform better, withdraw/consume less water, and flex according to water availability. This will require deep and imaginative reforms of irrigation water rights and legislation (Libecap, 2011) that match changing withdrawals to changing demands – and a spotlight put on unsustainable irrigation of non-food crops (WWF has highlighted this). Political, legal, economic, institutional and technical support for flexible frugal flourishing irrigation will be required across global food chains, governments, local councils, funders, research institutes, farmer groups and many other stakeholders – as well as the contracts, rules and institutions that govern decision-making. This principle reiterates that many deep-seated legacy protocols exist. For example, on the technical side, many irrigation engineers do not know about or value the second type/pathway given below; they are too dismissive of traditional irrigation (the 1st & 4th types) and too easily drawn towards the promise of automated pressurised drip irrigation, the 3rd type/pathway.

- Global and regional-scale co-ordination. A more systematic catchment approach to irrigated agriculture in a warming world would be complemented by regional and global assessments and coordination of irrigation, irrigated production and risks to that production. Although lots of uncoordinated irrigation systems seem to be superficially meeting global food needs, food insecurity is shaped by geography, inequality, poverty and gender (HLPE, 2023). In a less predictable future, we will need to know how to affordably feed the world’s population if large areas of irrigated agriculture (especially rice) are knocked out by floods and droughts. UN global food summits are supposed to be the vehicle for this but often show little interest in irrigated systems. This principle would cover a stocktaking of irrigation capacity-building and services. Also global food companies have a water stewardship role here, recognising flexible, frugal, flourishing embedded water in their value chains and contracts.

- Action research, knowledge brokers, peer-to-peer learning, mentoring and business support. This principle takes us to action-research and partnerships that work closely with and encourage systems, irrigators and groups of irrigators to be better prepared for the future. This principle understands that, by far, gatekeepers and farmers are the main water managers of global irrigation. More specifically, action research is needed to find what (e.g. smart-phone apps) or who (e.g. farmer leaders) might drive system transformation, and then how to scale this out via peer-to-peer partnerships and mentoring. This principle also includes non-technical services such as legal mapping, conflict management, and business/strategy training (e.g. book-keeping) for irrigators.

- Four types and pathways for integrated irrigation water control The above principles and their application depend on an understanding of irrigation for delivering water control. I believe there are four types or characterisations of integrated irrigation water control, given below. These types offer pathways for improving control within and across those types. In other words, we should be careful of applying automation (type 3) to type 1 systems without first considering type 2 pathway might be more appropriate.

- The first type is termed ‘field watering via water provisioning and distribution’. This first type describes many present-day small and large canal irrigation systems that provide water to fields using extant turnout and canal dimensions, and visual clues such as water levels to manage water. Yet on closer inspection this water conveyance and distribution is often without structure, tight water control or quantitative knowledge of water applications. Systems of this type see improvements – but these tend to be via one-off relatively uncoordinated measures such as land laser-levelling and canal lining. Options to better perform might involve switching to types 2 and 3 under irrigation revitalisation or modernisation programmes.

- Strict structured water supply-led and hydromodule informed irrigation (Lankford, 1992). Although not well known, I have explained them in this blog.

- Automated computerised flexible crop-water demand-led – which can be hydromodule informed. This is where individual crop and field water demands are assessed and utilised as the means to determine watering schedules. Such systems usually include row crops, computer control of water, use of sensors, pressurised and piped water distribution, and drip or sprinkler watering. ICID hosts presentations on this, usually defining it as modern or modernised irrigation.

- Landscape/ecological/cultural, proxy- or other-led. These are irrigation systems that are culturally and historically embedded within the landscape and are sometimes called traditional irrigation systems (Fernald et al., 2015). Examples include the long-standing acequias of New Mexico. ‘Proxy- or other-led’, means they currently distribute water using their own unique priorities, indicators and rules. What such systems might miss in terms of a quantitative approach to tight water sharing, they might gain in terms of flexibility, social transparency and acceptability, and priority given to other water uses such domestic provisioning. Such systems commonly experience periods of water abundance and drought and use these lessons to revisit water distribution and to become more climate-attuned, resilient / protective, and productive.

To find these types in their pure form is rare; most systems are hybrids. For example a mix of type 1 and 2 would be a very tight field watering design that did not use hydromodules but applied the dimensions of field area (ha), depth applied (mm) and duration (hours) to achieve accurate irrigation scheduling (e.g. 100 mm every 20 days on a fixed area replenishes 5 mm/day ETo + seepage). A mix of 2 and 3 would be a computerised, piped system where irrigation scheduling is supply-constrained rather than crop water demand-led. A mix of 3 and 4 might be an old hill irrigation system now adopting drip irrigation. All four forms cover either full or supplementary irrigation, the latter using a combination of rainfall and irrigation.

Discussion

Functioning not form. The difficulties and pressures irrigation faces in a warming world will be immense. This is means we need to look at irrigation anew. This is why the 15 principles are not interested in the superficial form or ownership of the irrigated system – whether it is large or small, or is commercial or farmer-led. Instead, the principles focus on multi-scale irrigation functioning to deliver improved water control over time and space, falling within and guided by the four main types and pathways of irrigation control.

Process-led. The 15 principles do not promote current fashions of irrigation per se – be they policy exhortations (“be more efficient”) or favoured interventions (e.g. pricing water, canal lining, metering, soil water sensors, solar). These run the risk of being single-scale expert-driven tinkering, or address supply management or demand management only. The emphasis is on a group analysis and improvement of integrated water control across large swathes of irrigated land in catchments – leading to carefully co-created new agreements, technologies, practices and infrastructure – and, if required, strategic / business training for irrigators to manage change.

An implementation programme. The 15 principles need packaging as a programme. I appreciate it won’t be easy to do this, and to switch away from current irrigation programmes (e.g. solar, farmer-led, modernisation). My answer is to start with catchment and system analyses to support farmers working together in smaller modular holons, in other words start with principles #14, #6, #10 and #11.

One risk is that, if packaged as a programme, the principles (especially #13) are seen as global top-down generalisations that have no local meaning or traction. On this, I am very clear about the unique nature of individual irrigated systems and their irrigators, and of the need to co-design and tailor services in order to prepare them for a warmer, more irrigation-complicated world.

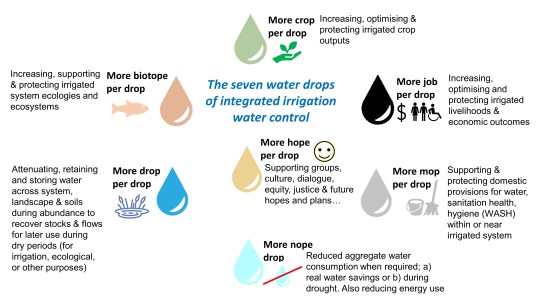

The seven drops. On a light-hearted note, the diagram below captures the seven drops of integrated irrigation water control; more crop per drop, more job per drop, more mop per drop, more nope drop, more drop per drop, more biotope per drop and more hope per drop. The aim of integrated irrigation water control is to determine how these seven are achieved, optimised, maximised, protected and balanced equitably during both normal/abundant and scarce drought periods.

Conclusion

To my mind, the 15 principles detail a significant water governance challenge; how to fit irrigated agriculture to a pressure-pot warming world, rigorously accountable to all. The 15 principles omit much – for example they do not cover other farming inputs or water quality. But they highlight a need for change. If ‘business as usual’ continues (water remains poorly controlled), irrigation will keep colonising freshwater, remain upstream of other sectors, be treated as the act of watering fields (Lankford and Agol, 2024), or be researched in an uncoordinated hobbyist fashion. Without a more-systematic approach to water control and irrigation, the sector will not be well placed to face a warming, fluxing, climate-turbulent, water-competing world yet maintaining a key role in growing food (and, where sustainable, other crops), supporting livelihoods, restoring soils, consuming less water and carbon-based energy – and/or banking more water in storage or for nature. Genuinely tough choices lie ahead; for example, the commons of groundwater irrigation (em)powered by solar presents a particular challenge.

Footnotes

Sincere thanks to Helen Rumford, Chyna Dixon, Arnald Puy, Saskia van der Kooij, Louise Busschaert, Mona Liza Delos Reyes, Stuart Orr, Nadja den Besten and Aaditeshwar Seth for helpful chats prior to this blog being published.

All views are my own. Nothing is new here. These principles omit more than they include. The citation is: Lankford, B.A. 2026. Principles for flexible frugal flourishing irrigation in a pressure-pot warming world; the need for integrated irrigation water control. https://brucelankford.org.uk/2026/01/19/flexible-frugal-flourishing-irrigation-in-a-pressure-pot-warming-world/

References

FERNALD, A., GULDAN, S., BOYKIN, K., CIBILS, A., GONZALES, M., HURD, B., LOPEZ, S., OCHOA, C., ORTIZ, M., RIVERA, J., RODRIGUEZ, S. & STEELE, C. 2015. Linked hydrologic and social systems that support resilience of traditional irrigation communities. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 19, 293-307.

HLPE 2023. Reducing inequalities for food security and nutrition. 2023. Rome: CFS HLPE-FSN.

LANKFORD, B. 2013. Infrastructure hydromentalities: water sharing, water control, and water (in) security. In: LANKFORD, B. A., BAKKER, K., ZEITOUN, M. & CONWAY, D. (eds.) Water security: Principles, perspectives and practices. London: Earthscan Publications, Routledge.

LANKFORD, B., AMDAR, N., MCCARTNEY, M. & MABHAUDHI, T. 2025. The iGains4Gains model guides irrigation water conservation and allocation to enhance nexus gains across water, food, carbon emissions, and nature. Environmental Research: Food Systems, 2, 015014.

LANKFORD, B. & BEALE, T. 2007. Equilibrium and non-equilibrium theories of sustainable water resources management: Dynamic river basin and irrigation behaviour in Tanzania. Global Environmental Change, 17, 168-180.

LANKFORD, B., CLOSAS, A., DALTON, J., LÓPEZ GUNN, E., HESS, T., KNOX, J. W., VAN DER KOOIJ, S., LAUTZE, J., MOLDEN, D., ORR, S., PITTOCK, J., RICHTER, B., RIDDELL, P. J., SCOTT, C. A., VENOT, J.-P., VOS, J. & ZWARTEVEEN, M. 2020. A scale-based framework to understand the promises, pitfalls and paradoxes of irrigation efficiency to meet major water challenges. Global Environmental Change, 65, 102182.

LANKFORD, B., MCCARTNEY, M. & HABETS, F. Forthcoming. REVISITING: Large dams water storage is unavoidable /or/ anathema. In: MOLLE, F. & BARONE, S. (eds.) Revisiting Best Practices in Global Water Policy – Questioning Water Mantras. Routledge.

LANKFORD, B., PRINGLE, C., MCCOSH, J., SHABALALA, M., HESS, T. & KNOX, J. W. 2023. Irrigation area, efficiency and water storage mediate the drought resilience of irrigated agriculture in a semi-arid catchment. Science of The Total Environment, 859, 160263.

LANKFORD, B. A. 1992. The use of measured water flows in furrow irrigation management — a case study in Swaziland. Irrigation and Drainage Systems, 6, 113-128.

LANKFORD, B. A. 2008. Integrated, adaptive and domanial water resources management. Adaptive and integrated water management. Springer.

LANKFORD, B. A. 2023. Resolving the paradoxes of irrigation efficiency: Irrigated systems accounting analyses depletion-based water conservation for reallocation. Agricultural Water Management, 287, 108437.

LANKFORD, B. A. & AGOL, D. 2024. Irrigation is more than irrigating: agricultural green water interventions contribute to blue water depletion and the global water crisis. Water International, 1-22.

LANKFORD, B. A. & MCCARTNEY, M. 2024. Managing the irrigation efficiency paradox to “free” water for the environment. In: KNOX, J. W. (ed.) Improving water management in agriculture: Irrigation and food production. Cambridge Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing Limited.

LANKFORD, B. A. & SCOTT, C. A. 2023. The paracommons of competition for resource savings: Irrigation water conservation redistributes water between irrigation, nature, and society. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 198, 107195.

LIBECAP, G. D. 2011. Institutional Path Dependence in Climate Adaptation: Coman’s “Some Unsettled Problems of Irrigation”. American Economic Review, 101, 64–80.

MALLAWAARACHCHI, T., AURICHT, C., LOCH, A., ADAMSON, D. & QUIGGIN, J. 2020. Water allocation in Australia’s Murray–Darling Basin: Managing change under heightened uncertainty. Economic Analysis and Policy, 66, 345-369.

ROSA, L. 2022. Adapting agriculture to climate change via sustainable irrigation: biophysical potentials and feedbacks. Environmental Research Letters, 17, 063008.

SIKKA, A. K., ISLAM, A. & RAO, K. V. 2018. Climate-Smart Land and Water Management for Sustainable Agriculture. Irrigation and Drainage, 67, 72-81.