Strict structured modular supply-led irrigation

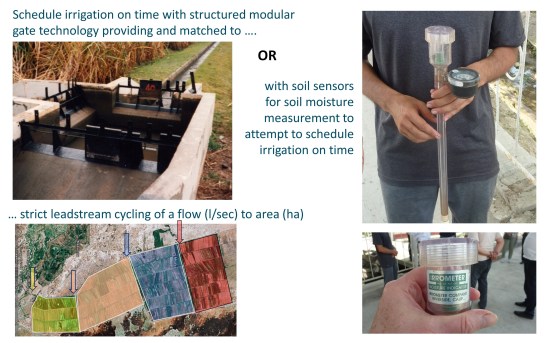

Many irrigation commentators observe two types of irrigation; traditional and modern (both come loaded with beliefs and baggage but that is not my point here). My point is there are other types of irrigation, including structured modular supply-led irrigation able to schedule accurate deficit irrigation using tight supply hydromodules (l/sec/ha). This type can deliver accurate irrigation, even during drought, without the need for drip technology or soil water sensors.

Before I dive into the explanation of modular supply-led irrigation, I first raise a concern about commentators referencing soil water sensors, believing them to be a sign of, or tool for, precision irrigation. However their recommendations do not come from practical experience, or a wide reading of the irrigation literature. For example, Mazzucato and von Burgsdorff write: “Data gathered from soil moisture sensors, weather stations, and satellite technologies allows for real-time adjustments to irrigation practices, enhancing precision and efficiency.” ** Page 22. Mazzucato, M., & Kühn von Burgsdorff, L. (2025).

Adding lots of soil water sensors to inform irrigation scheduling is a fruitless charade – especially for irrigated field crops on public and smallholder systems extending thousands of hectares. Here are six, amongst many reasons, why this is the case. Point sensors cannot capture in a statistically satisfying way soil moisture variability over time and space. They struggle to accurately tell the difference between readily (RAM) and total available moisture (TAM) which is important in order to irrigate prior to temporary wilting. Third, they don’t inform scheduling after a soaking rain because rotational irrigation often has to begin before RAM is depleted in order to be able to get round in time before the last field in the queue reaches wilting point. Fourth, they are an expensive logistical headache, requiring them to be reset and pulled out at the start and end of each season. Fifth, they negate social means for distributing water – which becomes increasingly important during drought. Lastly, and importantly, they licence or excuse the idea that irrigators must always meet crop water demands rather than accurately eke out and apportion a limited supply. It is this latter challenge that irrigation will face in a warming water-scarce world, and is why I believe an understanding of strict structured modular supply-led irrigation is needed.

To explain, I would like to bring in two lessons from my early career in irrigation. These lessons were acquired at a large-scale sugarcane irrigation system, called IYSIS, based in the northern lowveld of Eswatini/ Swaziland in the mid to late 80s. The two lessons can be connected to two people I worked with – Rod Ellis and Simon Gondwe.

Together they provide one possible future pathway for large-scale gravity canal irrigation systems.

Deficit irrigation and supply-led irrigation scheduling. (From Rod Ellis). Moving to Eswatini from the Zimbabwe sugar industry, which had gone through severe drought in the early 80s, Rod Ellis brought with him a remarkable philosophy towards irrigation. It was the essence of what I now term frugal flourishing irrigation. It basically says that when you have little water during a drought, then for a perennial crop like sugarcane you have to be highly structured in your approach to irrigation scheduling. This deficit supply-led approach applies and consumes less water, achieves satisfactory yields of sugar (which responds well to mild stress) and reserves stored water for later in the season (eking out water). Rod outlined this policy in this 1985 paper. Incidentally my first joint authored paper on deficit irrigation was with Rod, and it can be downloaded here.

A full account of Rod’s contribution to irrigation thinking in Southern Africa was organised by his son, Brendan Ellis – who asked AI Gemini to summarise Rod’s remarkable approach to irrigation. With permission from Rod, I am honoured to host this account on my website which can be downloaded here.

Tight, equitable and correct supply hydromodules. (From Simon Gondwe). After spending my soil science student year at IYSIS, I returned to the lowveld to become an irrigation agronomist. I was tasked with finding out whether we were over- or under-irrigating the sugarcane – a surprisingly difficult thing to do. That is a story for another time – but I did what all good soil scientists and irrigation agronomists do. I ran around trying to figure out soil moisture balances across 10,000 ha of sugarcane. We had rainfall gauges, several Class-A evaporation pans, tensiometers, soil augers and even a neutron probe. It all seemed the ‘right thing to do’ – but this is work-intensive and there is a better way of ‘doing the thing right’.

Summary; ‘doing the thing right’. In my last two years of my irrigation work took a different direction when one day Simon Gondwe, who was managing part of the surface/gravity irrigated sugarcane, asked me “why was his section short of water?” This quote is at the end of this paper that records the journey I then went on. Simon had worked out that his supply hydromodule in litres per second per hectare was lower than for other sections and this was harming his chances of scheduling on time, and ultimately his yields. It was, as they say, a light-bulb moment. What the papers and my blog on hydromodules indicate is ‘design in the right supply hydromodule ratio’ (l/sec/ha) using correct modular gate dimensions and command areas for peak water demand, and you don’t need to run around measuring soil water. And it very much fitted what Rod was introducing. For crops not in the peak season, then one simply irrigates less frequently. The trick always is how to get irrigation on-time during the hotter full-canopy peak periods especially when rainfall is lacking. And for that, we need precise irrigation scheduling hard-wired into the irrigation infrastructure.

References

Ellis, R. D., & Lankford, B. A. (1988). The tolerance of sugarcane to water stress during its main development phases. Agricultural Water Management, 17, 117-128.

Lankford, B. (1992). The use of measured water flows in furrow irrigation management – a case study in Swaziland. Irrigation and Drainage Systems, 6, 113-128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01102972

Ellis, R., Wilson, J., & Spies, P. (1985). Development of an irrigation policy to optimise sugar production during seasons of water shortage. Proceedings of the South African Sugar Technologists Association.

Mazzucato, M., & Kühn von Burgsdorff, L. (2025). A mission-oriented approach to governing our global water challenges and opportunities. IIPP Policy Brief 31. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/publications/2025/jan/mission-oriented-approach-governing-our-global-water-challenges